A Rigorous Study of the Secrets Buried Beneath the Welcome Mat

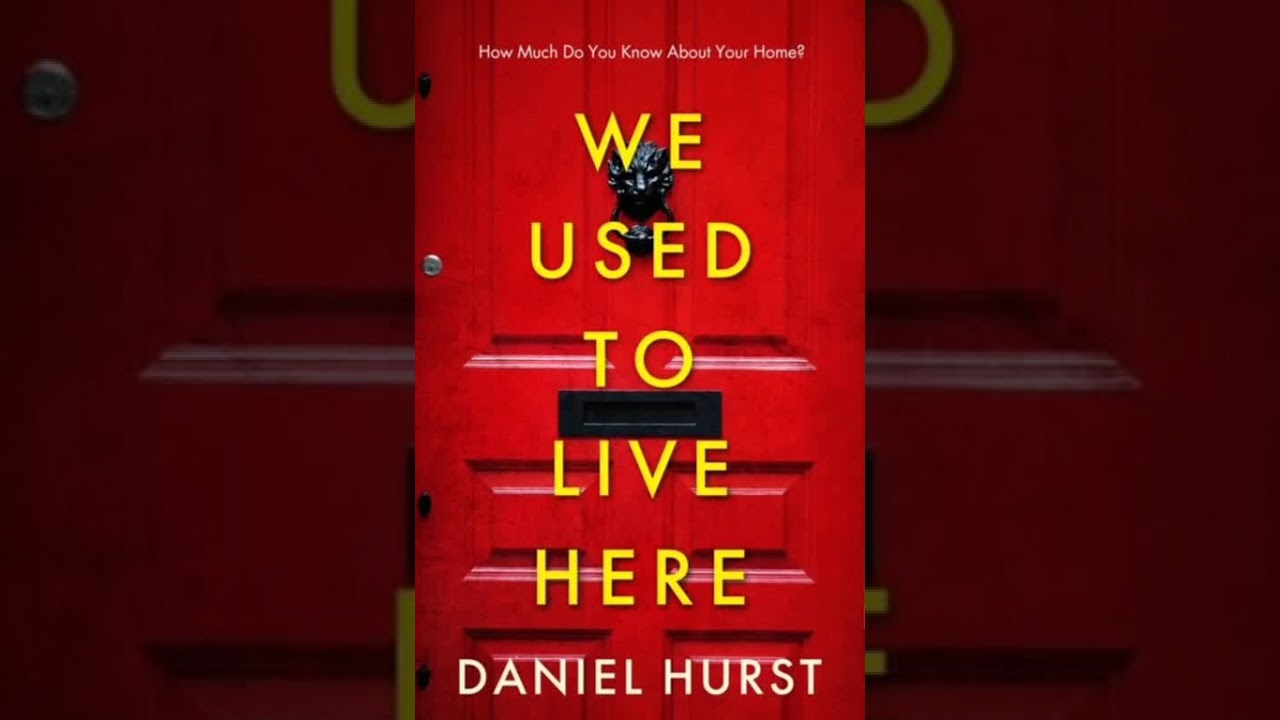

Does a house ever truly belong to its current owners, or is it merely an aggregate collection of the lives lived, the secrets kept, and the horrors buried by those who came before? Daniel Hurst’s We Used To Live Here strips away the veneer of the simple, aspirational dream of homeownership, replacing it with a creeping paranoia that will leave every beginner home buyer, intermediate homemaker, and digital professional questioning the stability of their own foundations. The narrative opens not with a welcome, but with the chilling afterload of a police investigation at 31 Birchfield Drive—a swarm of 17 people, sniffer dogs, and ground penetrating radar, all searching for a dead body in a “quiet street in an extremely quiet town” [00:14]. This is the great hook: before we even meet the protagonists, Steph and Grant, we know their future home is irrevocably linked to a past crime. Our goal here is not merely to review, but to educate and inspire by analyzing how this thriller dissects the modern anxieties of security, asset protection, and the psychological burden of a major life transition, while delivering a relentless, authoritative tempo of suspense. This review will greatly expand upon the mechanisms of this narrative, demonstrating why it serves as a powerful cautionary tale for all audiences.

The Psychological Preload of Homeownership and Hidden Liabilities

For many, buying a second home is the greatest financial and emotional investment, a transaction burdened by a psychological preload of high expectations, financial strain, and the hope for a fresh start. Steph and Grant, a couple with two young children, Charlie and Amelia, are seeking a larger space to accommodate their expanding family [06:05]. Their motives are pure, simple, and relatable: more bedrooms, more storage, and a playroom [06:10]. The viewing of 31 Birchfield Drive appears routine, conducted by an agent, Rose, as the current owners have opted to be absent [07:13]. This seemingly simple detail, however, immediately introduces a fundamental element of thriller writing—the creation of a vacant stage that the reader knows is hiding something.

The act of house viewing, which is normally a celebration of possibility, becomes an exercise in careful Concentration as the couple examines the exterior for “red flags” [05:13]. This mirrors the intermediate homemaker’s anxiety: is the house safe? Is the neighborhood sound? This preload of anxiety, already substantial, is then met by the external afterload of the house’s documented, hidden history, which includes a dead mistress buried in the garden, a fact revealed in a later segment [05:20:23]. This narrative structure masterfully explores two types of anxiety, respectively: the self-imposed stress of a major investment, and the external threat of an inherited trauma. The book teaches us that when acquiring a major asset, be it a physical home or a digital enterprise, the history, or chain of custody, is as important as the immediate state of the asset. Grant and Steph are forced to lay hold of a life that is perpetually shadowed by the results of others’ actions.

The Rigorous Mechanics of Suspense: Hurst’s Step-by-Step Delivery

Daniel Hurst’s craft in We Used To Live Here is a rigorous lesson in building suspense from seemingly mundane domestic events, allowing the narrative tempo to intensify with relentless Concentration. The author doesn’t rely on jump scares, but rather on the accumulation of small, unsettling details that function like psychological time bombs:

Case Study: The Austere Demand for Cleanliness and Compliance

During the initial viewing, the real estate agent, Rose, politely but firmly asks Steph and Grant to remove their shoes [08:46]. This seemingly simple request—a chaste nod to maintaining the current owners’ property standards—serves a double purpose in the suspense genre:

- Immediacy of Vulnerability: Removing their shoes immediately places the potential buyers in a position of literal and figurative discomfort. They are momentarily stripped of their defenses and asked to comply with an arbitrary rule in an unfamiliar space.

- A Simple Anchor of Compliance: This sets a tempo for the future relationship. The homeowners are still exerting control, even in their absence. This echoes a common issue for digital professionals when inheriting a new system: immediately being subjected to austere, non-negotiable legacy protocols that feel strange but must be followed.

Case Study: Decoding the Relics of the Past

Once Steph and Grant move in, the great task of redecorating begins, providing the perfect vehicle for Hurst to surface the buried secrets. As they scrape wallpaper, they uncover a forgotten message: a love heart and the initials “K and J” [30:11]. This relic immediately inspires Steph to “fantasize about who Kay and Jay could be” [30:35]. The message is no longer theirs; it belongs to the house’s history.

This anecdote is a powerful cautionary tale for the digital professional. When inheriting a legacy system or network infrastructure, the aggregate history—old, forgotten configuration files, unused database tables, or hard-coded credentials left by “Kay and Jay”—represent significant hidden liabilities. The message itself holds no monetary value, but it has immense sentimental and narrative value [29:56]. The action Steph takes is to refer to this message, not dismiss it, recognizing its importance as a “little time capsule” [30:11]. This demonstrates a key lesson: the importance of a rigorous system audit to uncover and decommission historical, non-relevant data that could become a vulnerability or a clue.

The Two Types of Buried Secrets: A Study in Systemic Failure

The sheer complexity of the hidden horrors elevates We Used To Live Here beyond a simple domestic thriller. The house, 31 Birchfield Drive, is a repository for two distinct types of crimes, respectively, demonstrating how multiple layers of tragedy can accumulate over time within a single system:

- The Aggregate Crime of the Current Owners (Steph and Grant’s Preload): This is the greatly publicized crime discovered in the prologue: the husband of the previous owner, Grant, had killed his mistress and buried her body in the garden [05:20:28]. The buyers, Simon and Helen (in a later iteration of the story), got the house cheaply because of this chilling discovery [05:20:02]. This introduces the theme of asset depreciation due to latent risk. The discovery is immediate, violent, and highly public—the afterload is the inevitable property devaluation.

- The Hidden Crime of the Older Past (The Deep Legacy): The final, chilling revelation takes the horror back even further to an even earlier set of occupants, Ken and Julie. Beneath the floorboards of what had been Charlie’s playroom, Simon’s son Ralph accidentally loses a paper plane [05:21:12]. This simple action uncovers the final, darkest secret: a small skeleton, the remains of “the boy who had never ran away” [05:22:31]. This skeleton—the ultimate aggregate of the house’s hidden, unacknowledged history—represents the deep, un-audited legacy of a system.

The contrast between these two types of horror—the publicized crime that drops the price, and the hidden crime that threatens the foundations—is the great masterstroke of the book’s delivery. It shows that while one can refer to public records for a known problem, the most devastating liabilities often reside in the neglected, unseen spaces.

Practical, Step-by-Step Advice from the Thriller: A Chaste Checklist for Home and Digital Security

The authoritative insights of We Used To Live Here can be translated into practical, step-by-step instructions for our diverse audience, serving as an inspiration for proactive risk mitigation. The book is linked to real-world anxieties about privacy and security, and we must pluck the lessons from the fictional horror.

I. The Homeowner’s Rigorous Vetting Checklist (Intermediate Homemakers)

Before you seize a new property, you must lay hold of all available data, not just the visible structure.

| Step | Actionable Tip (Inspired by 31 Birchfield Drive) | Rank of Importance | Key Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Deep Audit the Grounds: Go beyond public records. Hire a rigorous specialist to inspect areas normally neglected (shed foundations, old fence lines, deeply sheared soil beds). The “gardening joke” that turned real serves as a warning [05:19:47]. | High | Concentration |

| 2. | Vetting the Sellers’ Intent: Note the tempo and rates of the sale. If the house sells “very competitively” and the owner wants a “quick sale” [05:20:16], understand the financial afterload that drove that urgency. It’s often distress, which can greatly increase hidden risks. | High | Tempo |

| 3. | Investigate the Neighbors: They are the aggregate history keepers. Politely but firmly ask about the house’s reputation, not just the street’s. The neighbors speculated on the body search, confirming the results were public knowledge [01:40]. | Medium | Aggregate |

| 4. | Demand Subsurface Disclosure: Refer to the law (which exists to protect citizens) and require disclosures on all previous major renovations, particularly regarding floorboards (where the skeleton was found) or unusual foundation work [04:23]. | High | Refer |

II. The Austere Digital Security Protocol (Digital Professionals)

Steph and Grant’s failure to conduct a deep “system audit” is analogous to inheriting a compromised digital system.

- The Simple Rule of Legacy Code: When inheriting an old system, treat any simple, chaste relic (like a hidden, polite message or a forgotten file) as a potential security risk. Old, unmaintained code runs at different rates and may introduce shear stress on the new system. Do not just paint over it; decommission it entirely.

- The Rigorous Data Scrub: All previous owners’ data—even seemingly benign items like height markings on a door frame (the growth records they “left behind” [29:44])—must be scrubbed. For a professional, this means ensuring that all cloud accounts, software licenses, or configuration files from previous employees are wiped, not just archived. The risk of data leakage dissipately spreads across the network if left unmanaged.

- The Concentration on Vulnerability Scans: Do not rely only on perimeter security (the front door/firewall). The skeleton was found deep inside, under the floorboards—the literal foundation of the system. This requires great Concentration on internal vulnerability scans and penetration testing of core structures. The most devastating results come from deep-seated, linked liabilities.

The Great Delivery of the Politely Disruptive: The Elderly Visitors

The escalating paranoia in We Used To Live Here is perfectly embodied by the seemingly simple appearance of the elderly couple on Steph and Grant’s doorstep [56:47]. This anecdote serves as a chilling example of boundary invasion, a fundamental fear for the homemaker and a serious threat for the digital professional.

When the elderly people appear, they look “almost as surprised to see us as we are to see them” [56:53]. The man is about to knock, his gesture polite and benign. However, the unexpected arrival greatly disrupts Grant and Steph’s planned tempo of leaving, forcing them to stop in their tracks. This chaste intrusion is far more effective than a violent one. It uses social convention to lay hold of their attention and paralyze their movement.

- For the Homemaker: This is a lesson in establishing austere, clear boundaries. The most persistent, linked threats often present themselves in the most simple, seemingly innocent packaging. You must be prepared to politely but firmly pluck yourself out of a situation that disrupts your safe tempo.

- For the Digital Professional: This is the most common form of social engineering—the great act of using a non-threatening persona to seize access. The “elderly couple” is the phishing email, the unexpected vendor, or the colleague who politely asks for a password reset over the phone. The results of this simple intrusion can be catastrophic. The only defense is a rigorous adherence to protocol, regardless of the perceived “friendliness” or chaste nature of the request.

Conclusion: Concentration on the Unseen Past

Daniel Hurst’s We Used To Live Here is a great work of psychological suspense that uses the universal dream of a perfect home to explore the aggregate horror of inherited legacy. The book greatly succeeds because it makes us realize that every new beginning comes with a historical preload and a potential afterload of unresolved crises. For our audience, the rigorous, step-by-step delivery of the plot offers an authoritative simple truth: security—whether for a house or a system—requires Concentration not just on what is visible, but on what has been dissipately hidden, forgotten, and buried.

This novel is more than a thriller; it’s a practical reminder that before you can seize a future, you must refer to, audit, and reconcile with the deepest secrets of the past. The results for Steph and Grant are devastating, but the results for the reader are an inspired, greatly heightened sense of Concentration on their own security.

Call-to-Action: If this analysis has unsettled the simple notion of “home sweet home,” then you must pluck this book from the digital shelf. Let the relentlessly increasing tempo of Hurst’s narrative inspire you to perform your own rigorous audit—both of your digital assets and the literal ground beneath your feet.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Is the book suitable for a beginner to the thriller genre? A: Absolutely. The book is structured clearly, making it easy for a beginner to follow the tempo and the dual plot lines. Hurst’s delivery is simple and highly accessible, and the domestic setting makes the tension greatly relatable. The terror is psychological rather than gratuitous.

Q: How does the book use the setting to create tension? A: The setting of a newly purchased family home is what creates the greatest preload of anxiety. The house itself acts as an aggregate character—a vessel that holds the secrets of its previous occupants. The tension is created through simple contrasts: a well-manicured lawn vs. the mud bath of the crime scene [00:41], and the need for a “playroom” vs. the skeleton hidden beneath the floorboards [05:21:01].

Q: What is the most important takeaway for a digital professional? A: The most important lesson is rigorous legacy auditing. The aggregate secret of the skeleton under the floorboards represents the most dangerous types of digital risk: the old, forgotten, deep-seated liability that no one remembers to refer to. This requires Concentration on deep system penetration testing, not just superficial security checks. The results of a good audit are worth the time and financial afterload.

Q: The book seems dark; does it end on an austere note? A: Like many psychological thrillers, the delivery is not a traditionally “happy” one, but it is deeply satisfying. The great power of the book lies in the unraveling of the truth, which offers a dark form of clarity. It is a rigorous look at how past actions cannot be dissipately forgotten, and the tempo of the final reveal is one of the most memorable elements.

Q: Where can I refer to more works by Daniel Hurst? A: Daniel Hurst is known for his domestic thrillers and uses a very simple, clear style. A simple search for his other works will give you great results, as he often explores themes linked to betrayal, home security, and hidden neighbors, allowing you to maintain a chaste and rigorous exploration of this genre.